By: Kamrin Baker

Feminist writer Virginia Woolf is famously quoted as saying: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” Erasure of women’s contributions in history is no new concept, but the act of identifying those women and sharing their stories of radical success has infiltrated the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

The women of Omaha’s history—still living or long gone— have found their voices through Tammie Kennedy, UNO’s director and editor of the Women’s Archive Project.

Kennedy, an associate professor in the English department who has her PhD in rhetoric, composition and the teaching of writing, has spent much of her scholarly career researching remembering practices.

When presented with the opportunity to help preserve the stories of UNO women through the original Women’s Centennial Project in 2011 (initially started by Sue Mahr), Kennedy jumped at the chance to lead a new student-produced archive. Through some further development, the project was reborn into the Women’s Archive Project.

“Much of my creative work focuses on the rhetoric of remembering practices and how the embodied qualities of memory shape identity, writing, and knowledge production–especially in feminist spaces,” Kennedy said. “I also took care of my grandmother for several years, and I realized the power of remembering women’s stories—all women, not just the famous or exceptional one.”

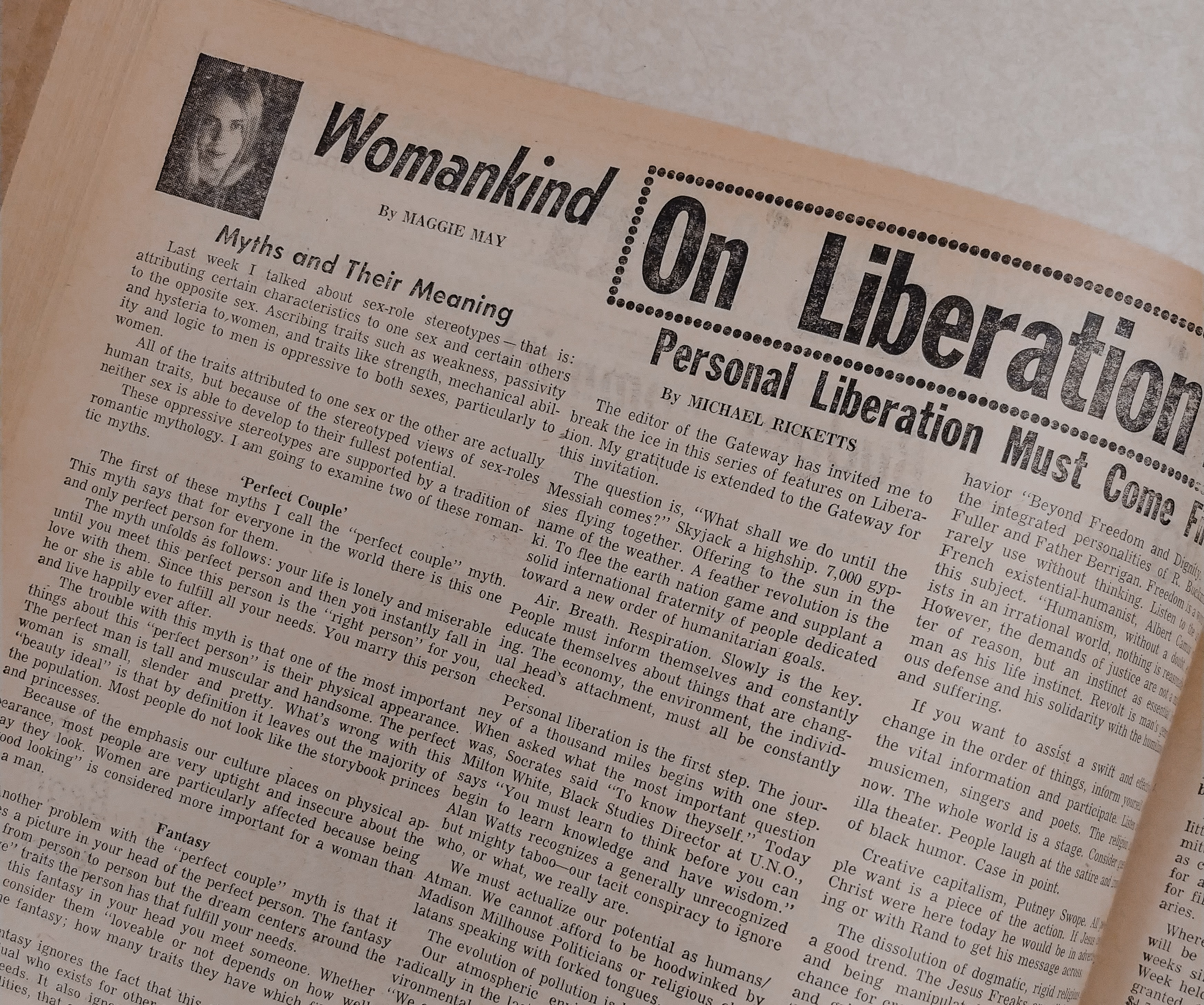

While not all stories are required to be exceptional, most of the profiles in the WAP certainly may be perceived as such. There is Ruth Diamond, who brought modern dance to all genders at UNO; Maggie May, an anonymous columnist who wrote the ‘Womankind’ section in the Gateway Newspaper during the second wave feminist movement; Claudia Gallaway, UNO’s very first and sole graduate in June of 1911; W. Meredith Bacon, the first openly transgender professor at the university; and many more.

These profiles are studied and written by students in the English department’s Writing Women’s Lives course, as well as individual web interns. The biggest limitation, Kennedy said, is funding.

This project seeks to recover the wide range of experiences of UNO-affiliated women throughout the decades,” Kennedy said. “That said, many times the recovery process is financial. The WAP has very little funding and when we do get donations, it’s temporary. We would be able to cover more stories if we had more funding and students who wanted to be involved.”

There is an option on the WAP’s website for family and community members to sponsor a profile of a loved one who meets the requirements for the archival project, and aside from some presentations, the project dwells entirely online. Much of the information that leads to the final profiles can be found in Archives and Special Collections in the UNO Criss Library.

Amy Schindler is the director of Archives and Special Collections, and the WAP was one of the first projects she was introduced to during her interview process at UNO.

“I remember being impressed by Dr. Kennedy’s vision and passion for the project,” Schindler said.

Schindler has collaborated with the contributors to the project in many capacities, including a Wikipedia Edit-A-Thon that focused on “improving the Wikipedia pages of women associated with UNO,” she said.

“It is critically important that this exclusion [of marginalized communities] be acknowledged and understood by repositories, so that they can move forward with building archives and other cultural heritage collections that truly represent and document communities in all of their diversity and with as much nuance as possible,” Schindler said. “If we do not understand the past in all of its complexities, then we will struggle to make sense of our present and the future.”

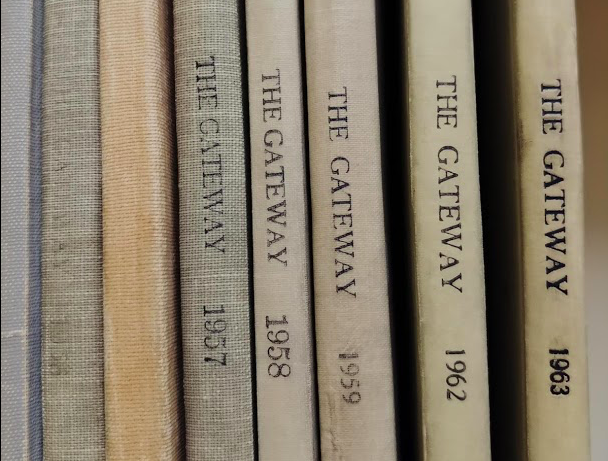

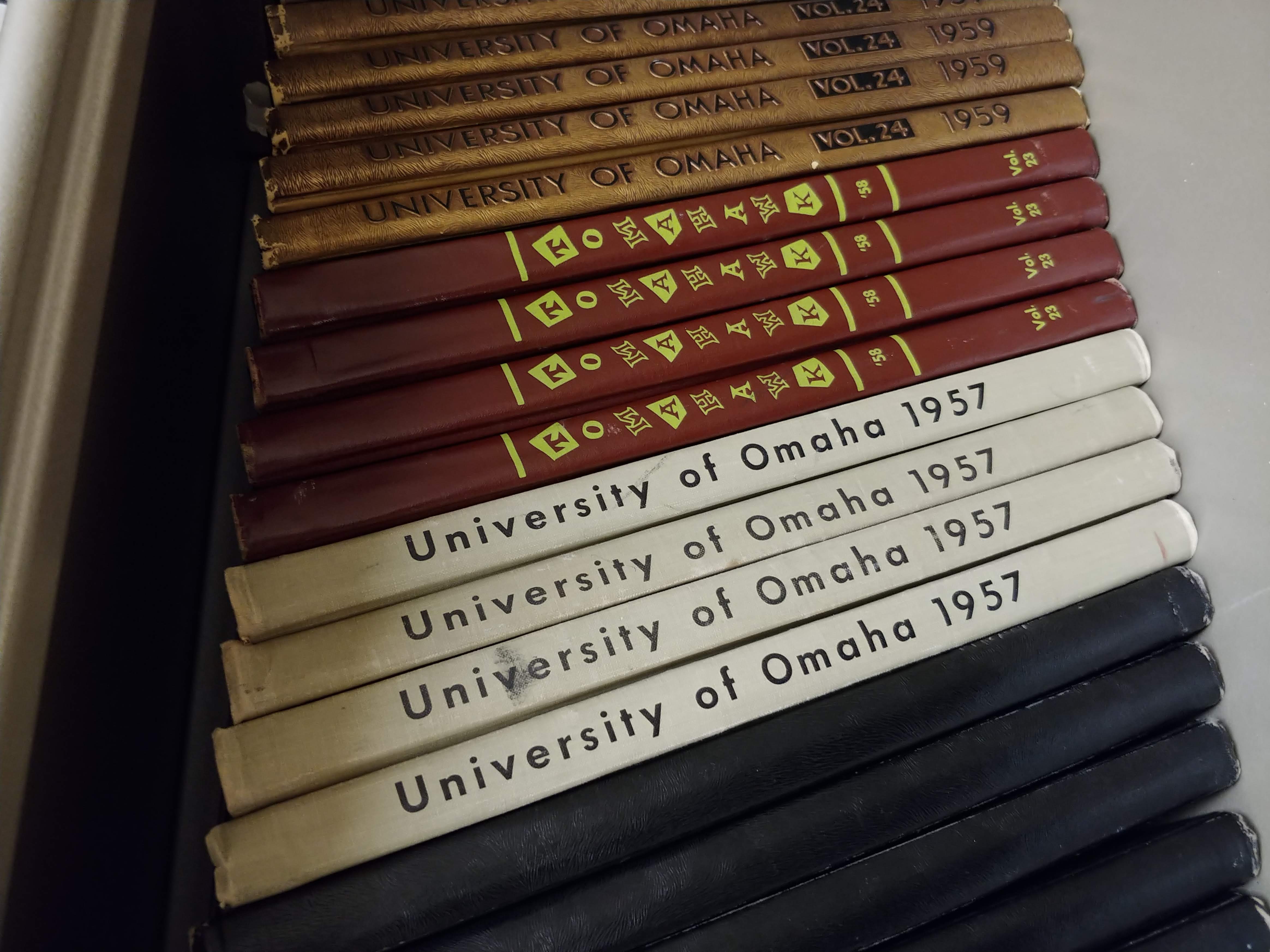

The most practical option for researching these women who are affiliated with UNO and its history is to turn to the pages that document history as it happens. Many researchers and writers who work for the WAP conduct interviews to develop a rich background in their profiles but find their starting points in the Gateway Newspaper and Tomahawk yearbooks.

These small, UNO-centric publications are perhaps the best metaphor for the project: these stories are worth telling, as they unfold, as they conclude—and as they remain in the past.

Kennedy explores the worthiness behind the stories of women in her journal article, “Pedagogy for Ethics of Remembering: Producing Public Memory for the Women’s Archive Project,” which was co-written with Angelika Walker of the College of Business Administration.

She wrote: “Being conditioned with indirect lessons of female inferiority had been a regular part of my education. Men had been the history keepers, the storytellers, and the gatekeepers of public memory for centuries, Suddenly, I recognized that histories could not be taken for granted any longer; things I already ‘knew’ must be reconsidered from marginalized perspectives.”

But what is the affect of reconsidering those histories? How does the community benefit from the work of the WAP?

“This is a very big question,” Kennedy says. “I will quote Muriel Rukseyer: ‘What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.’”

The women documented in the WAP are quite literally our neighbors, friends and teachers. Scrolling through their stories, it leaves one with a single lingering question: what will the current class of women affiliated with UNO do to open the world?